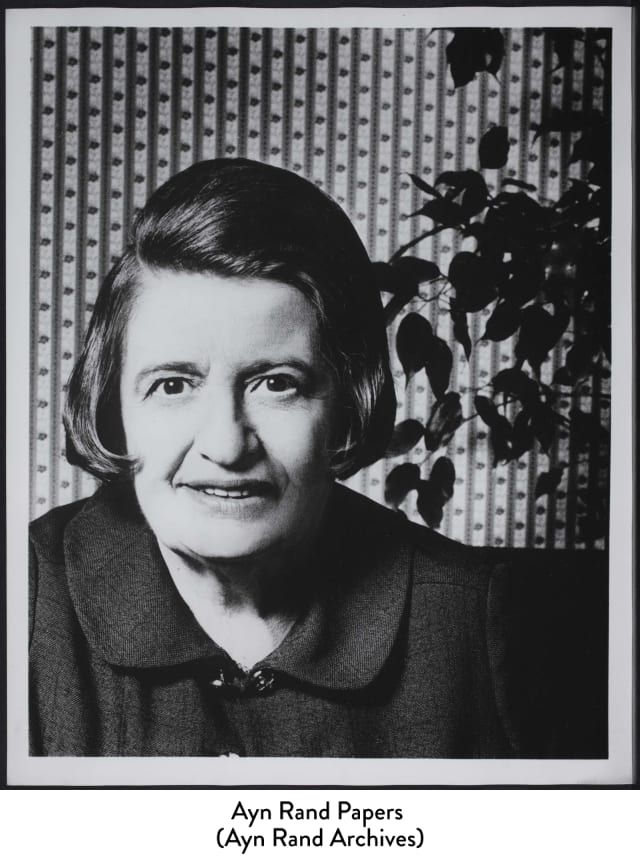

I am often asked whether I am primarily a novelist or a philosopher. The answer is: both. In a certain sense, every novelist is a philosopher, because one cannot present a picture of human existence without a philosophical framework; . . . In order to define, explain and present my concept of man, I had to become a philosopher in the specific meaning of the term.

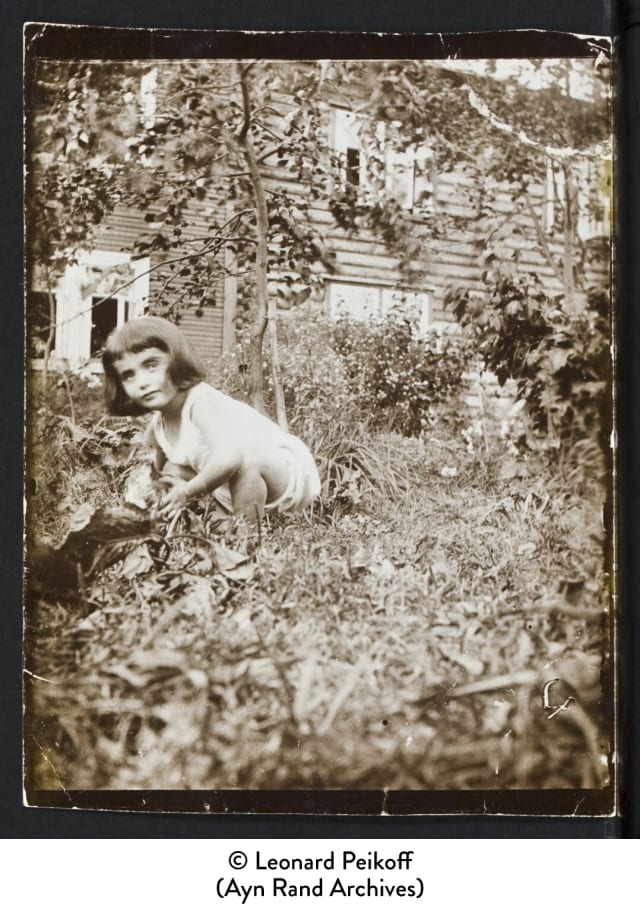

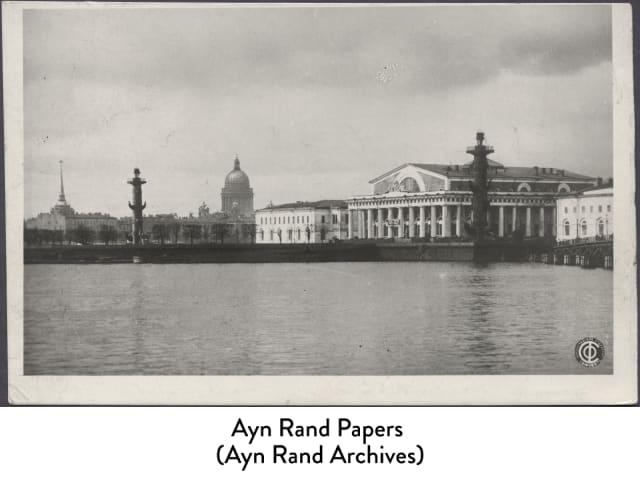

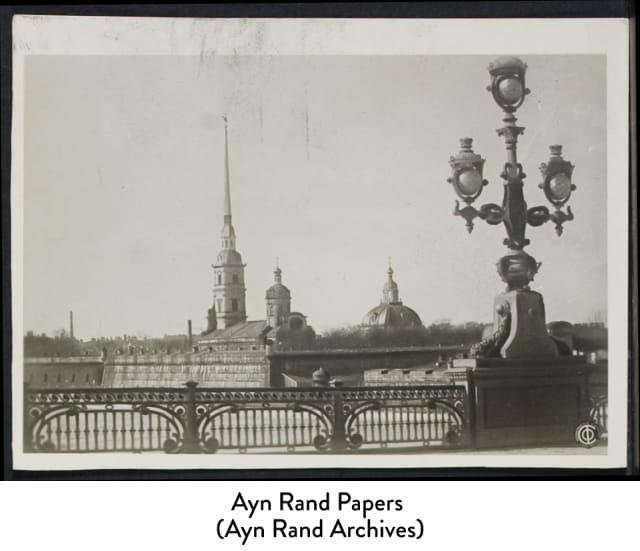

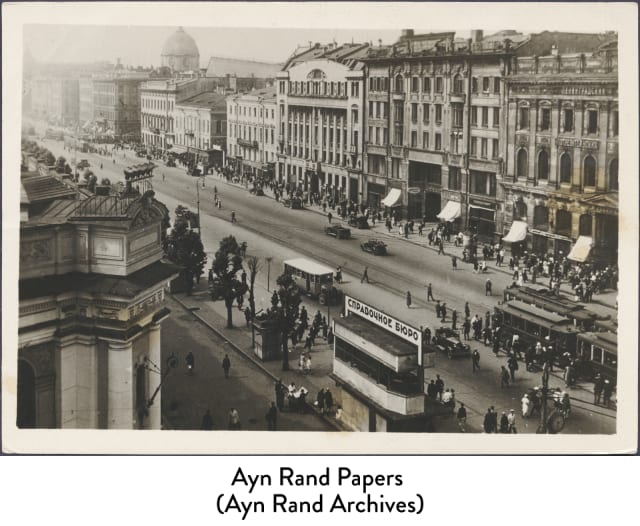

Ayn Rand was born Alisa Rosenbaum on February 2, 1905, in St. Petersburg (later Petrograd, then Leningrad), Russia. She hated the religious mysticism of Russia, later calling the country “an accidental cesspool of civilization.” But St. Petersburg was an exception, the cultural center of Russia and a window on Western civilization. Influenced by the Enlightenment, the arts and education flourished. It was in this atmosphere that the young Alisa taught herself to read (at age six), began asking “why” about the world around her, and developed a policy she called “thinking in principle.”

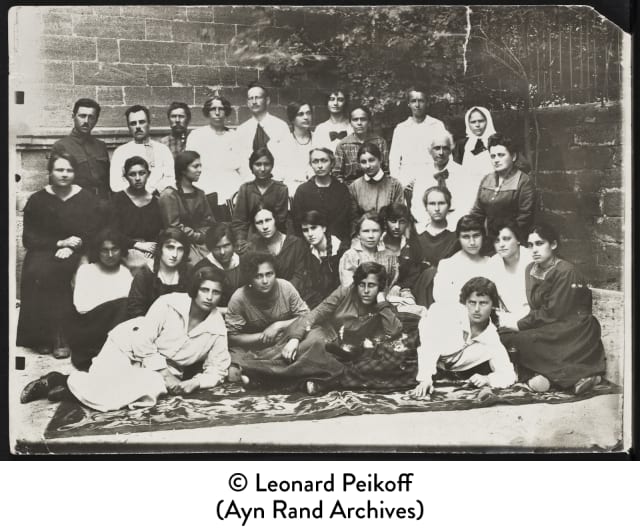

Alisa’s parents were from upper-middle-class Jewish backgrounds but the Rosenbaum home was nonreligious. Her father Zinovy was a successful pharmacist, and her mother Anna was a teacher and held intellectual salons at home. Both parents valued education and encouraged their children to be independent and purposeful: everyone, wrote Anna, “is the maker of his own happiness.” At age nine Alisa decided to become a writer. Her younger sister Natasha was an accomplished piano student, and her youngest sister Nora became a successful exhibit and graphic designer.

From an early age, Alisa wrote film scenarios and stories depicting heroic characters accomplishing great deeds. “I did not start by trying to describe the folks next door,” she would later say. What she had in mind was “a blinding picture of people as they could be.” In this quest she was inspired by exciting stories such as The Mysterious Valley, which she read in French, and by writers such as Walter Scott, Edmond Rostand and, especially, Victor Hugo, because he wrote about important things and projected “the grandeur of man.”

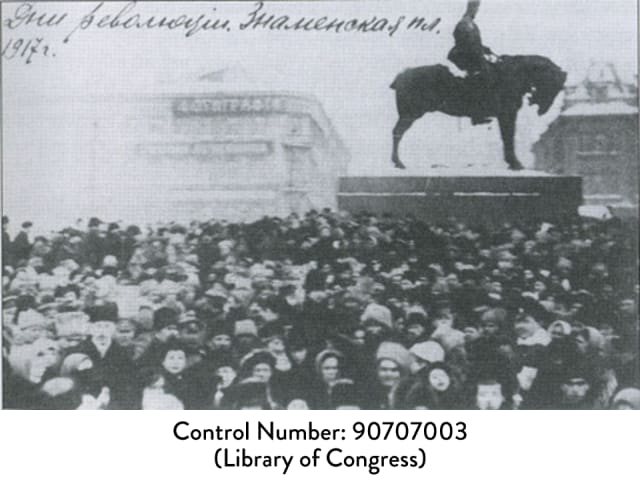

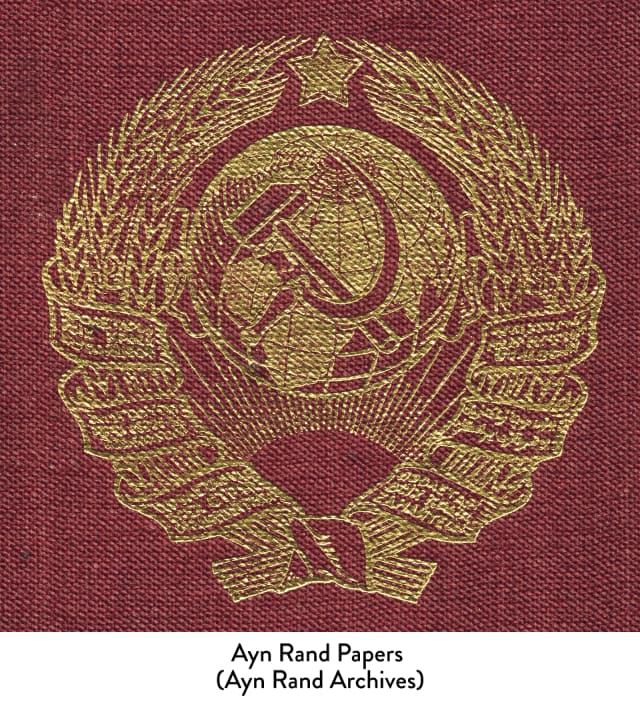

As she got older, Alisa became increasingly interested in politics, which she often discussed with her father. From the window of their apartment, she witnessed the first shots of the Russian Revolution in February 1917. First was the non-Communist revolution led by Alexander Kerensky, whom Alisa admired. But then came the Bolshevik Revolution that brought tyranny to Russia. Even at age twelve, Alisa was repelled by the Bolsheviks’ insistence that the individual must live for the state.

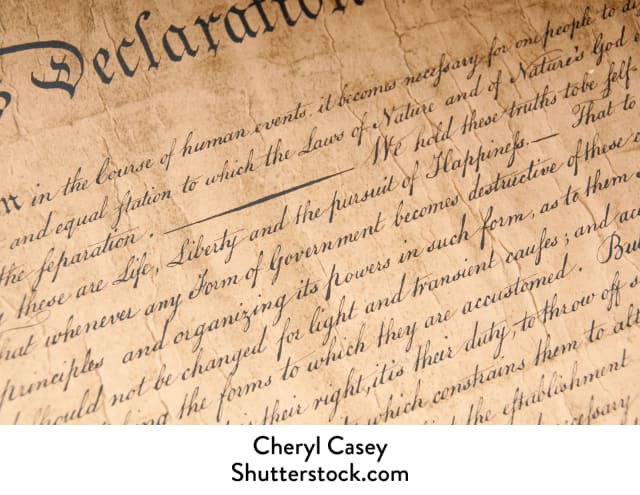

To escape the fighting during the Revolution, Alisa’s family fled to Crimea, where she finished high school. When introduced to American history in her last year of gymnasium, she immediately took America as her model of what a nation of free men could be. It was also in 1917 that she began a philosophic diary, analyzing a wide variety of basic philosophic issues. She later burned the diary, because its anti-Communist ideas could have meant a death sentence. The final Communist victory in Russia brought the end of her father’s career as a pharmacist and periods of near-starvation.

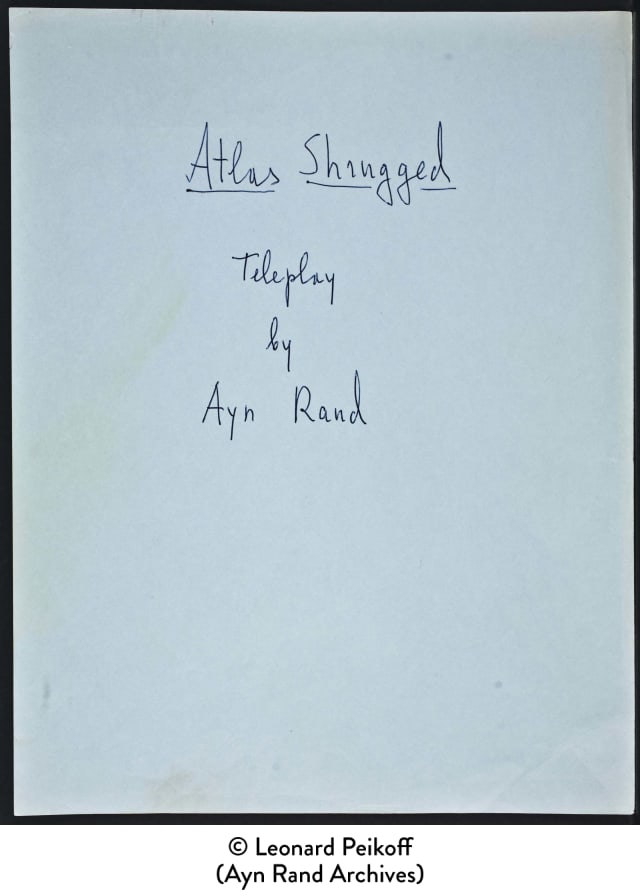

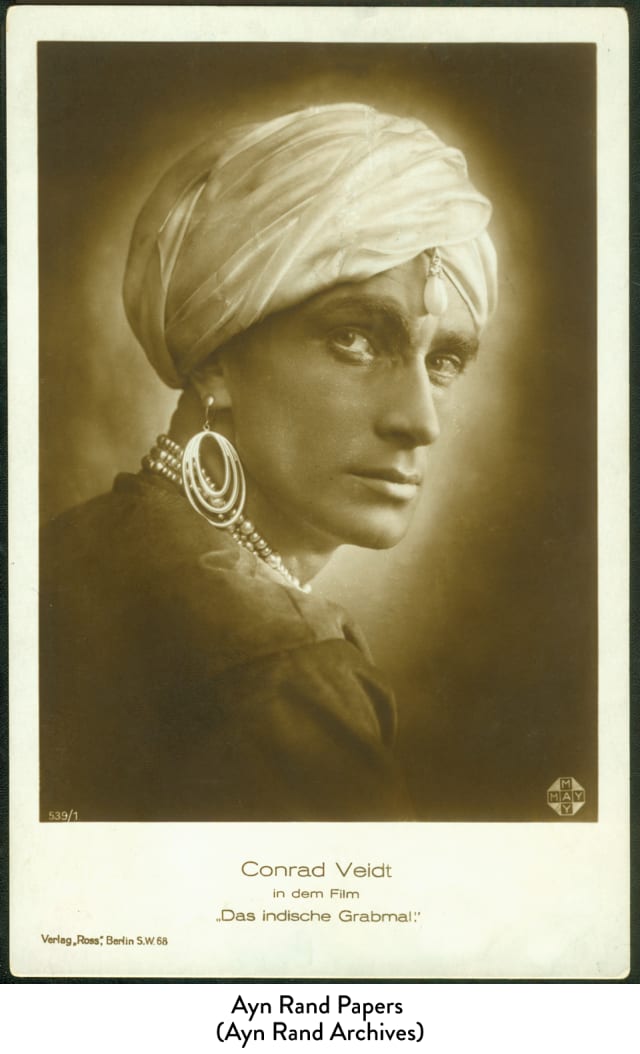

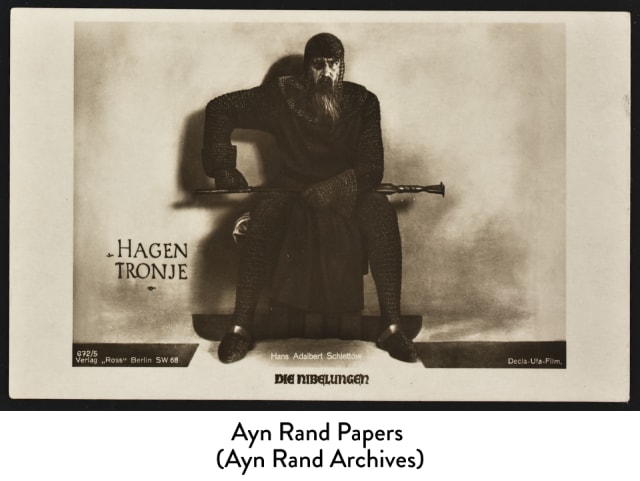

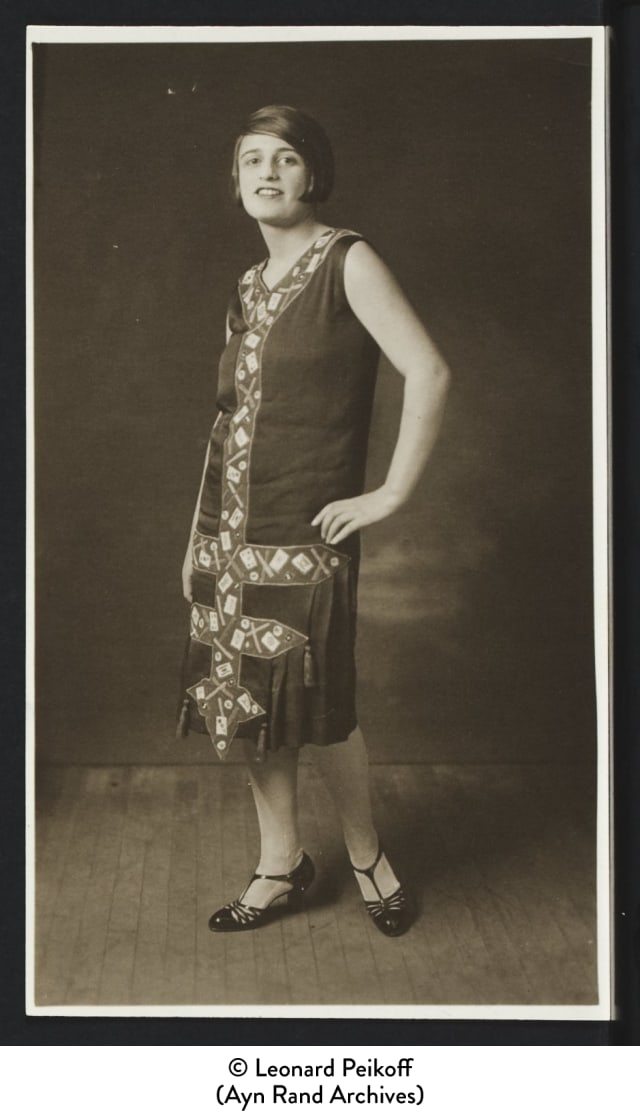

When Alisa’s family returned from the Crimea, she entered the University of Petrograd to study history and philosophy. Graduating in 1924 she experienced the destruction of free inquiry and the takeover of the university by gangs of communist students. Long an admirer of cinema (she even kept a film diary), she entered the State Institute for Cinema Arts in 1924 to study screenwriting. It was then that she was first published: a booklet on actress Pola Negri (1925) and a booklet titled Hollywood: American Movie City (1926), both reprinted in 1999 in Russian Writings on Hollywood.

During this period Alisa discovered a “spiritual escape” from Soviet Russia: Viennese and German operettas, which she could afford to attend only by saving her streetcar fare and walking to school through the harsh Russian winters. Operetta “was my first great art passion. That really saved my life. It was the most marvelous benevolent universe . . . the one positive fuel that I could have. My sense of life was kept going on that.” But foreign films began to supplant operettas as her main inspiration, because they were “a much more specific, not merely symbolic, view of life abroad.”

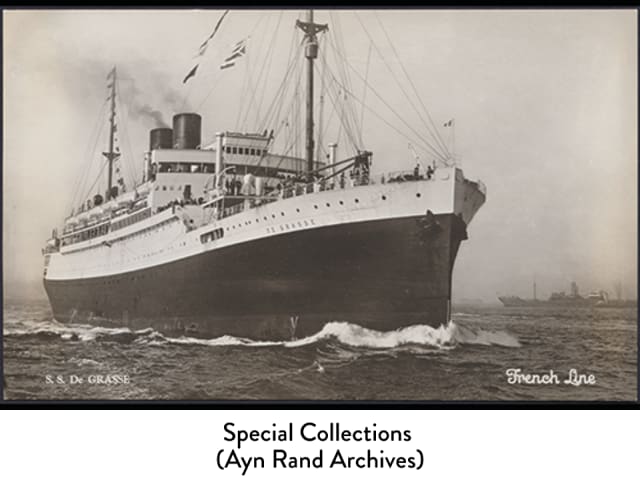

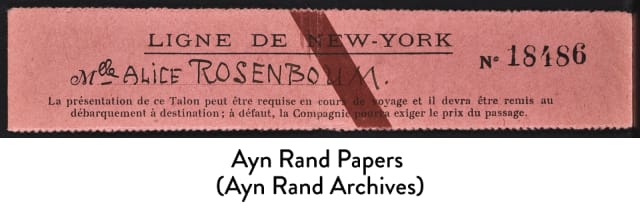

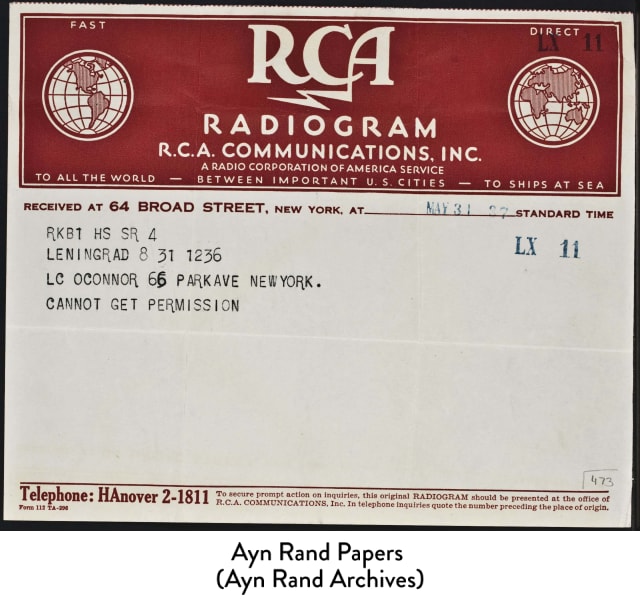

In 1925, Alisa’s mother arranged for her to visit relatives in Chicago. Alisa told Soviet authorities that she was going to America to learn filmmaking in order to help build the Soviet film industry. But she had no intention of ever returning to Russia. (She later commented that had she remained and written “her kind” of [pro-individualist] screenplays, she “would’ve been dead within a year.”) She left Leningrad on January 17, 1926, celebrated her 21st birthday in Berlin, and on February 10, sailed for New York from France. A few weeks later, the Soviets forbade such visits. After leaving Russia, Rand’s father predicted she would leave a mark and become world famous.

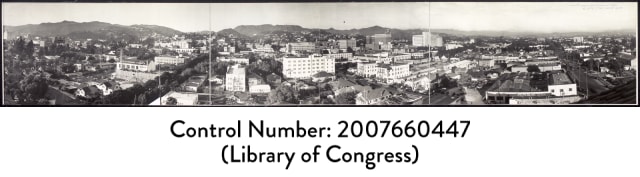

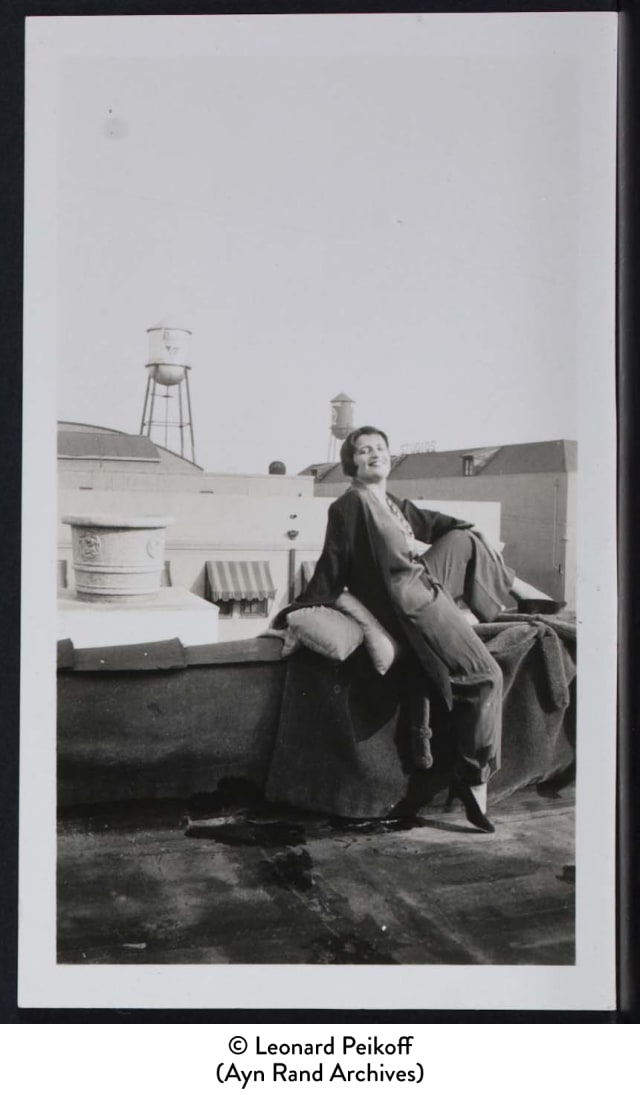

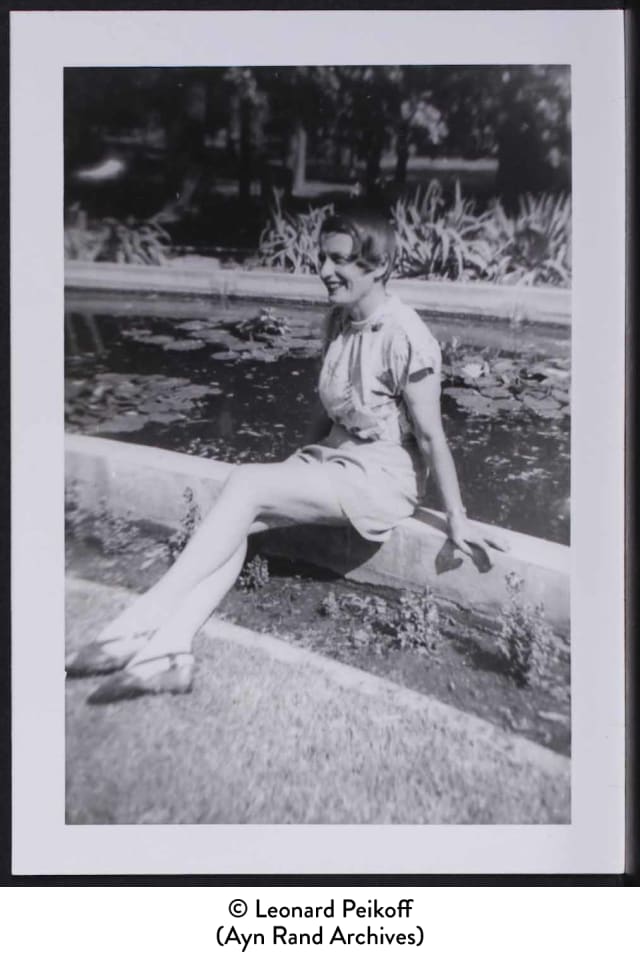

On February 19, 1926, Alisa arrived in America, the seemingly unattainable country and her ideal of individual liberty. After living with her Chicago relatives for six months, she left for Hollywood with an introduction to DeMille Studios, and a new name: Ayn Rand. On her second day in California, she had a chance meeting with Cecil B. DeMille, her favorite American director, who soon hired her as a film extra and then a writer. In 1929 she got a job in RKO Radio Pictures’s wardrobe department but quit in 1932 when she sold a scenario, “Red Pawn,” to Paramount Pictures. Her career had begun.

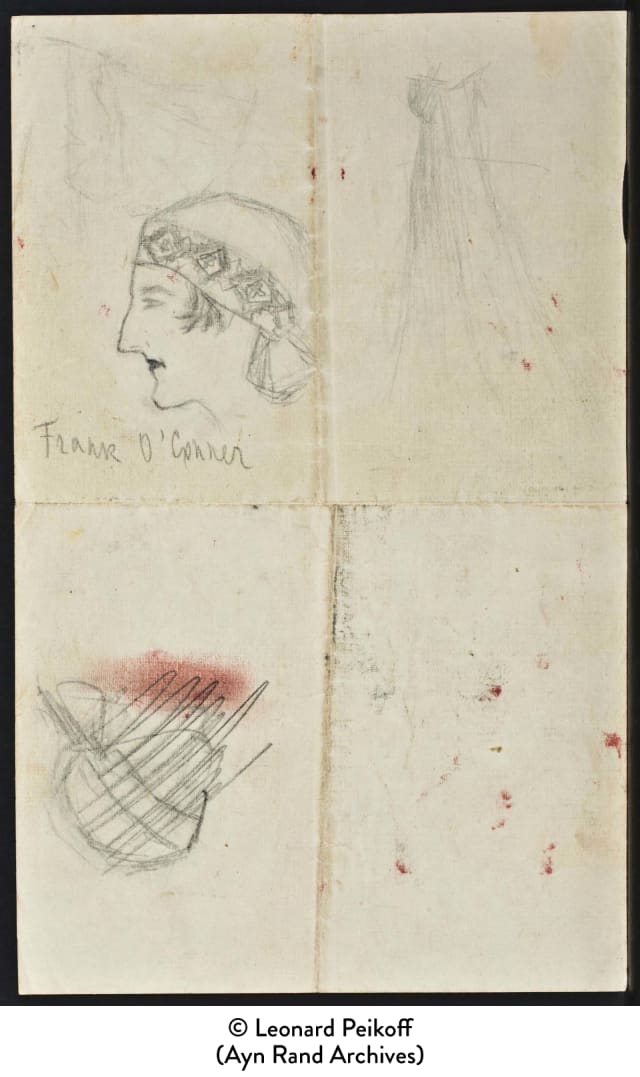

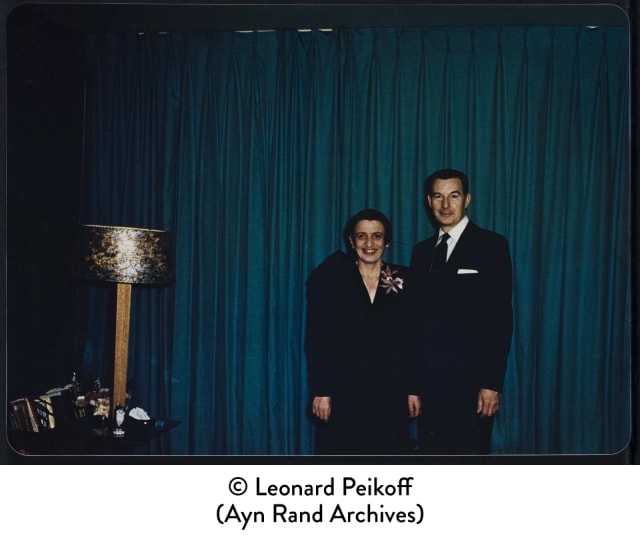

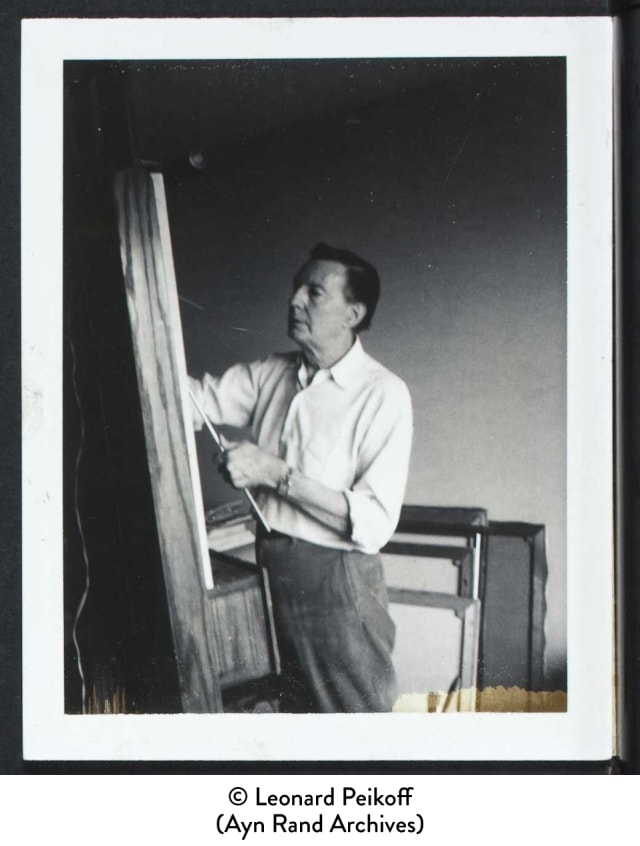

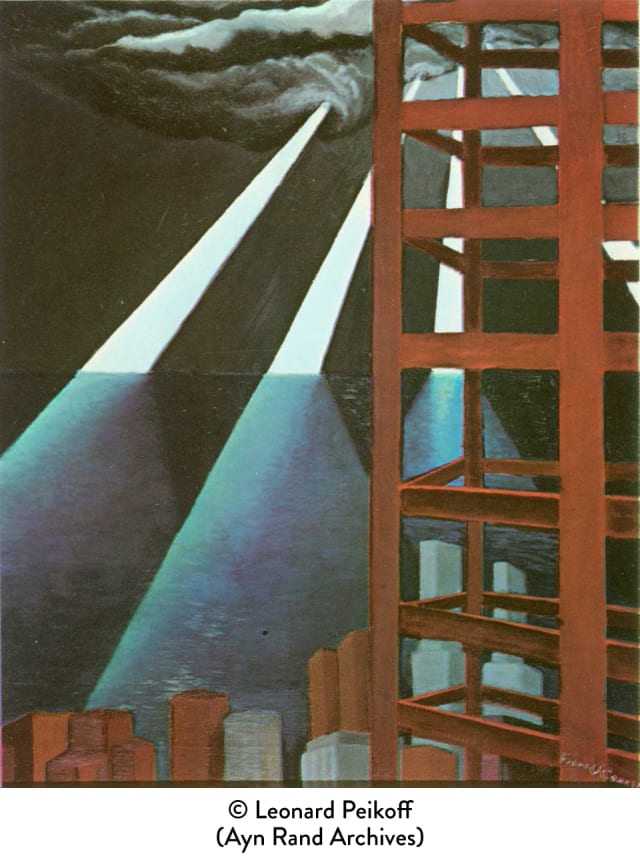

On her first bus ride to DeMille Studios, Rand had been captivated by a fellow passenger. She ran into him (literally) on the backlot of The King of Kings. He was actor Frank O’Connor. Losing track of him when shooting ended, she met him by chance at the Hollywood library; they began dating and were married on April 15, 1929. They were married until Frank’s death in 1979. “All my heroes will always be reflections of Frank,” she said. After a brief film career and many jobs, Frank became an artist in the 1950s. Rand described his paintings as “laughter let loose in the universe.”

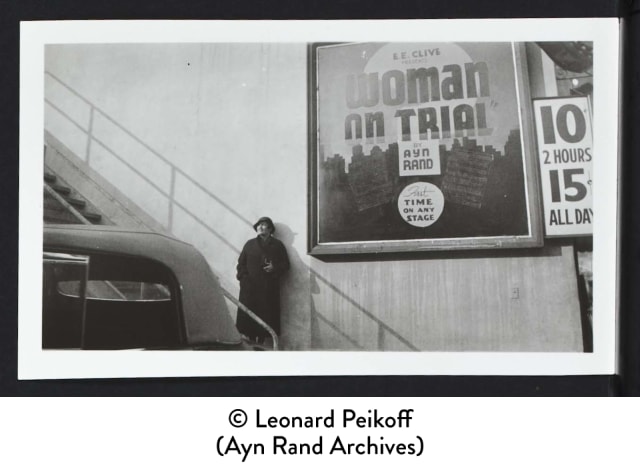

In 1933, while working on some long-range projects, Rand got the idea for a play about a murder trial whose verdict is determined by a jury selected from the audience. Night of January 16th would become her first commercial success. A well-received Los Angeles production (called Woman on Trial) was followed in 1935 by a Broadway production that ran for 29 weeks. Though frustrated at battles to preserve her script and disappointed by the final production, she nevertheless was thrilled to see her name in lights. Her career was taking off.

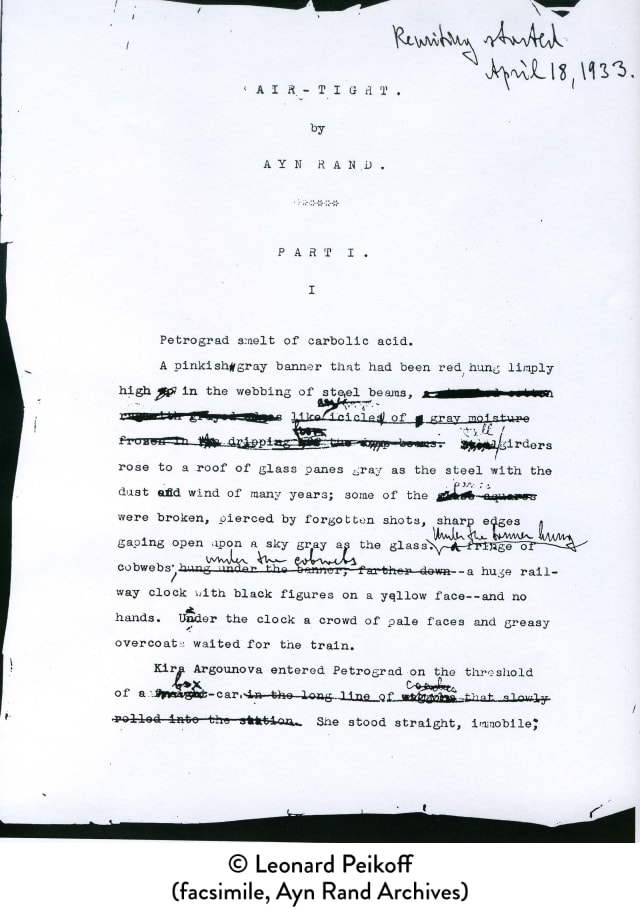

After years of hard work, Rand finished her first novel, We the Living, in 1934. Set in Soviet Russia, it is her most autobiographical novel. Its theme is one that was important to her since childhood: the evil of the belief that the individual should live for the state. At her going-away party in St. Petersburg in 1926, a guest asked her to tell everyone in America that “Russia is a cemetery and we are slowly dying.” With the publication of We the Living in 1936 (despite opposition from pro-Communist editors), she had told Americans.

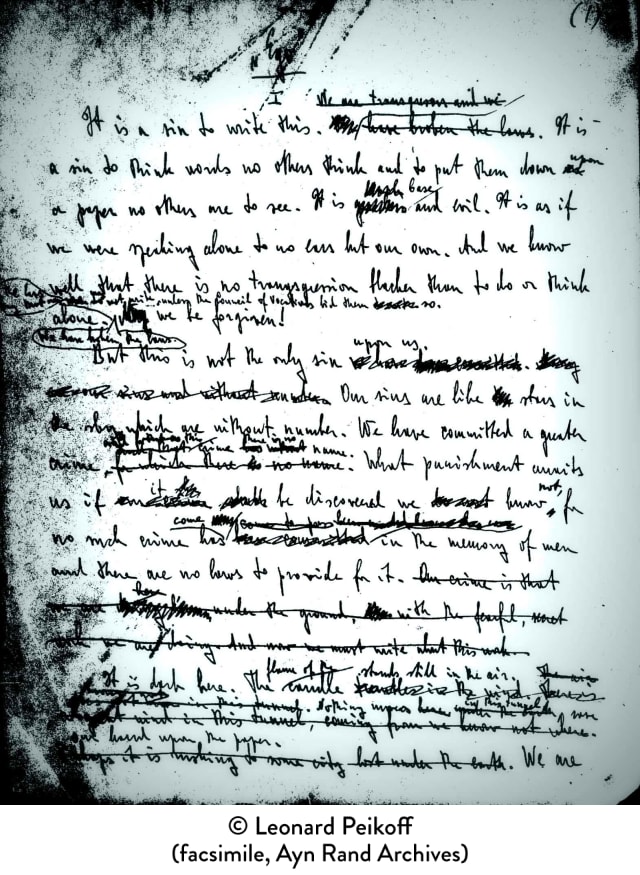

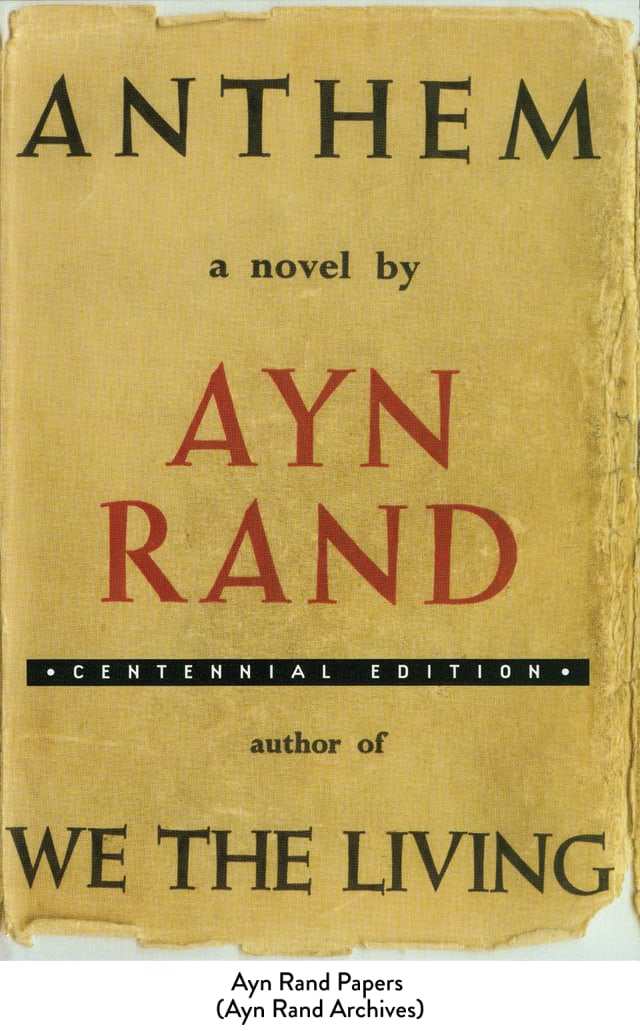

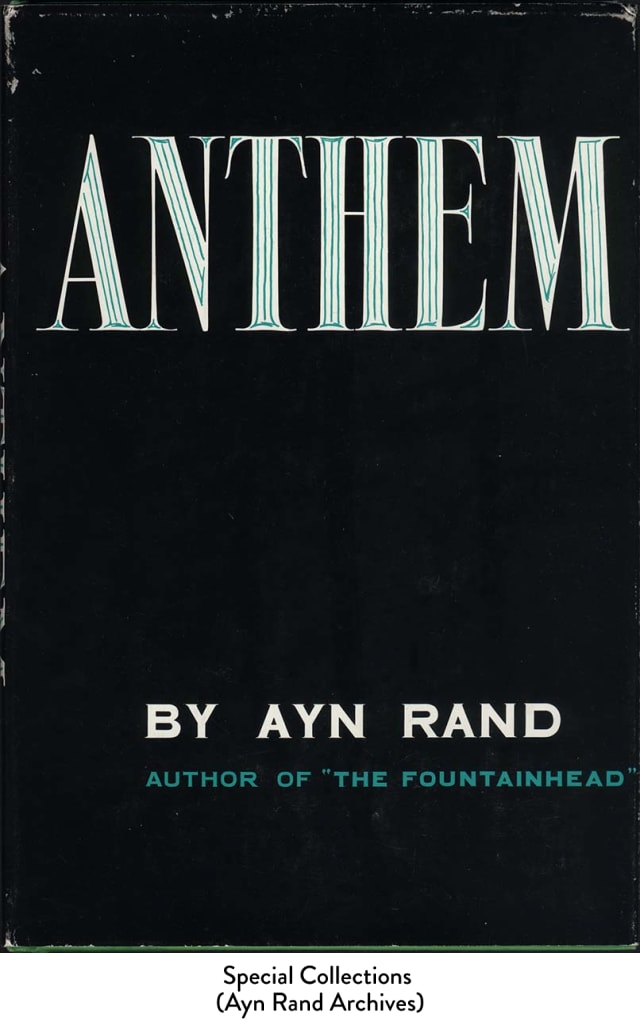

While taking a break from difficulties in working out the plot of her next novel, The Fountainhead, Rand spent two weeks writing a poetic novella she called Anthem. Based on a science fiction story she had conceived while in Russia, its theme is “the meaning of man’s ego,” a theme she projected into a world that had lost the very word “I.” The book was rejected by many American publishers, one of whom reported that the author didn’t understand socialism. Ironically, it was published in semi-socialist England in 1938 but not in America until 1946.

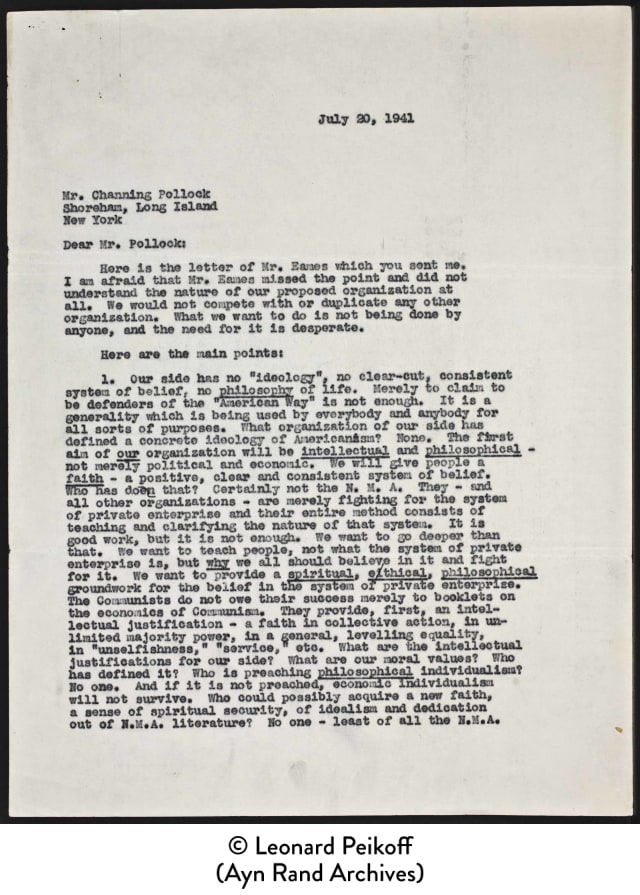

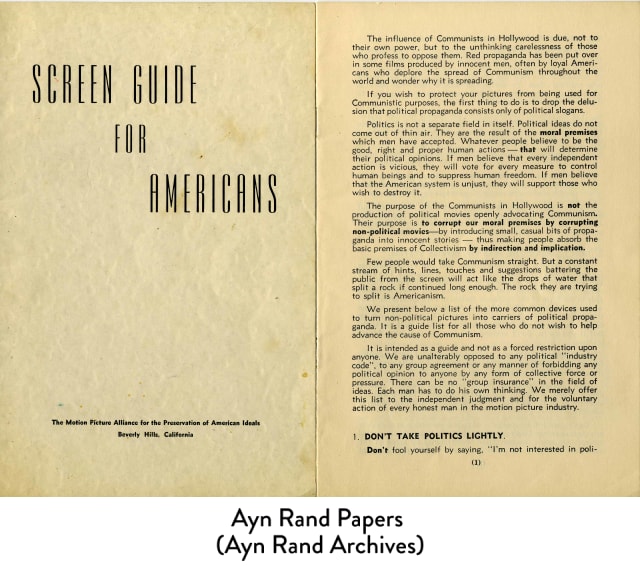

When Rand came to the United States, she expected to find a country devoted to individual liberty. What she found was intellectual domination by collectivism, the ideology of the country she had escaped. Her activism began in 1936 with a talk warning of the dangers of Soviet Russia and continued with her work for the Wendell Willkie 1940 presidential campaign, where she answered questions in a Manhattan theater. She later engaged Broadway playwright and critic Channing Pollock in a failed attempt to form an “individualist organization” that would carry her political views to the public.

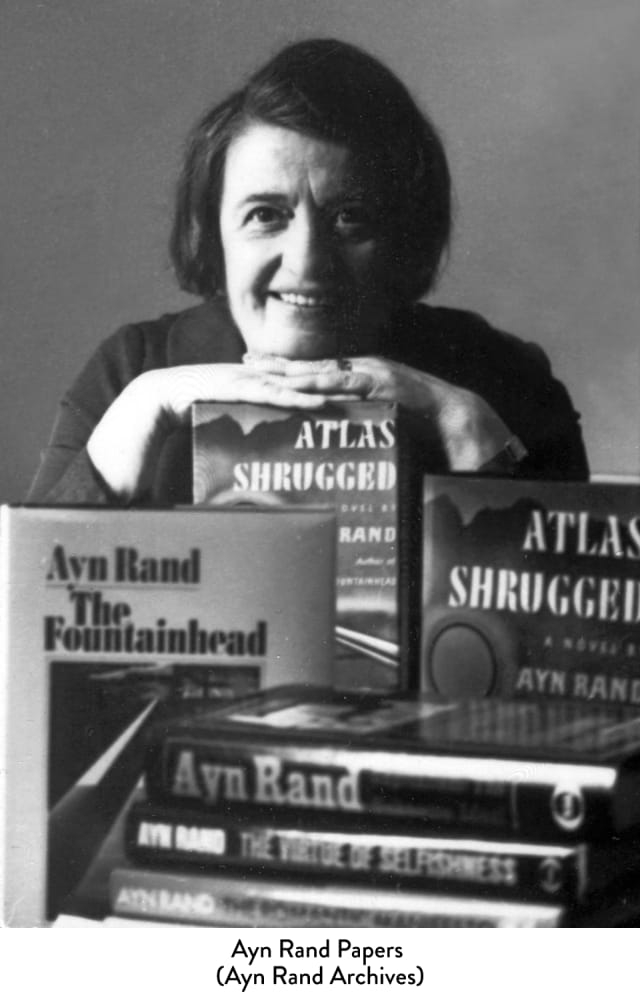

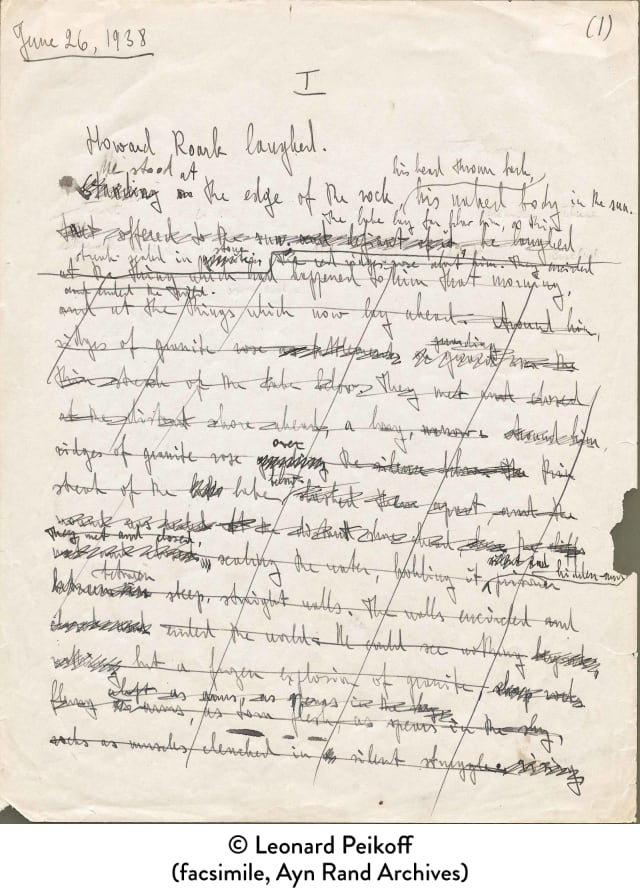

The story of a modern architect who sets his own standards, The Fountainhead’s theme is “individualism versus collectivism, not in politics, but in man’s soul.” It is Rand’s first presentation of her ideal man—her reason for becoming a novelist—and is the book that made her famous. On the best-seller list for more than fifty weeks, it reached #6 two years after publication, and, in 1949, was made into a successful film starring Gary Cooper. The novel’s enduring popularity, she wrote in 1968, lies in its appeal to “the sense that one’s life is important” and “that great things lie ahead.”

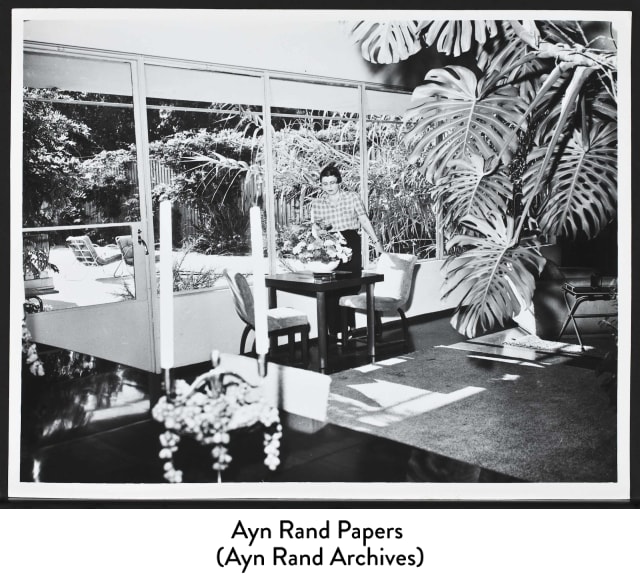

In late 1943 Rand sold the film rights to The Fountainhead. She and Frank then left her beloved Manhattan and returned to Hollywood to write the screenplay. What she hoped would be a short stay turned into another eight years in California, during which she wrote numerous other screenplays and completed The Fountainhead script, which was produced in 1949. After almost purchasing Frank Lloyd Wright’s Storer House, the O’Connors bought the Richard Neutra-designed Von Sternberg House, where Frank raised flowers and peacocks. Rand was now far removed from the poverty of Soviet Russia.

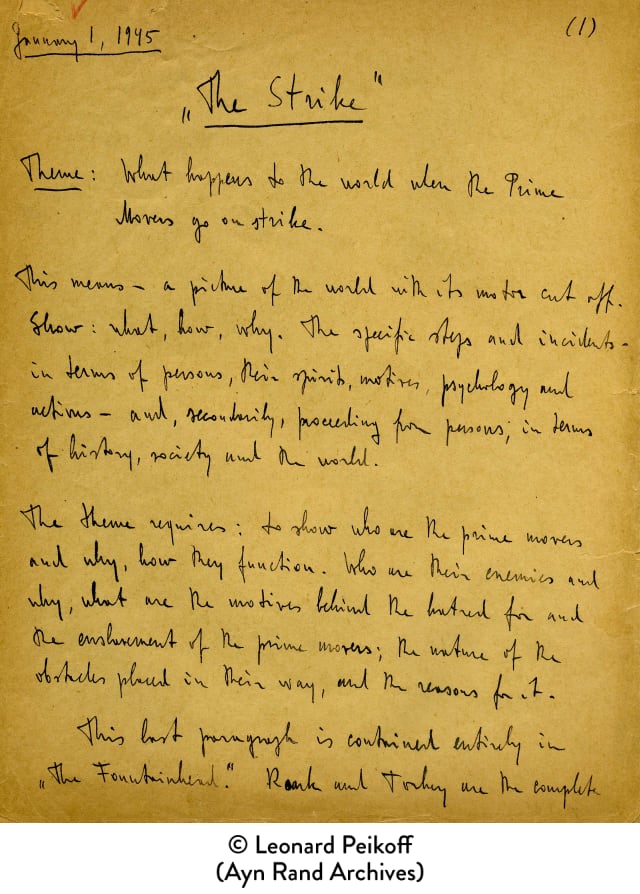

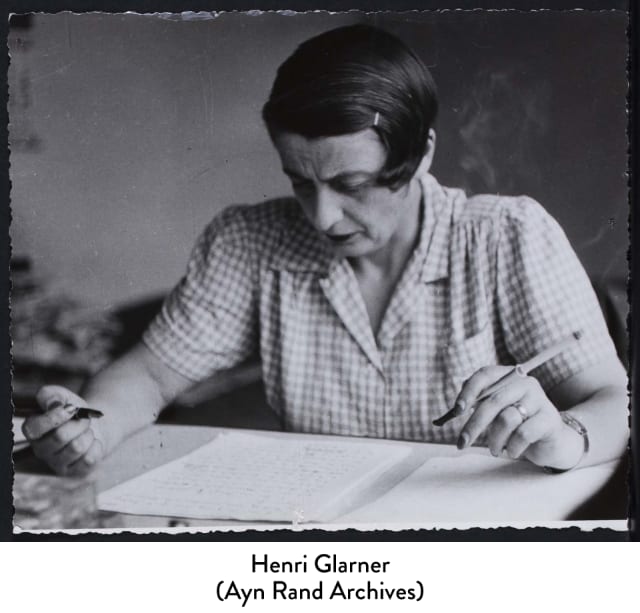

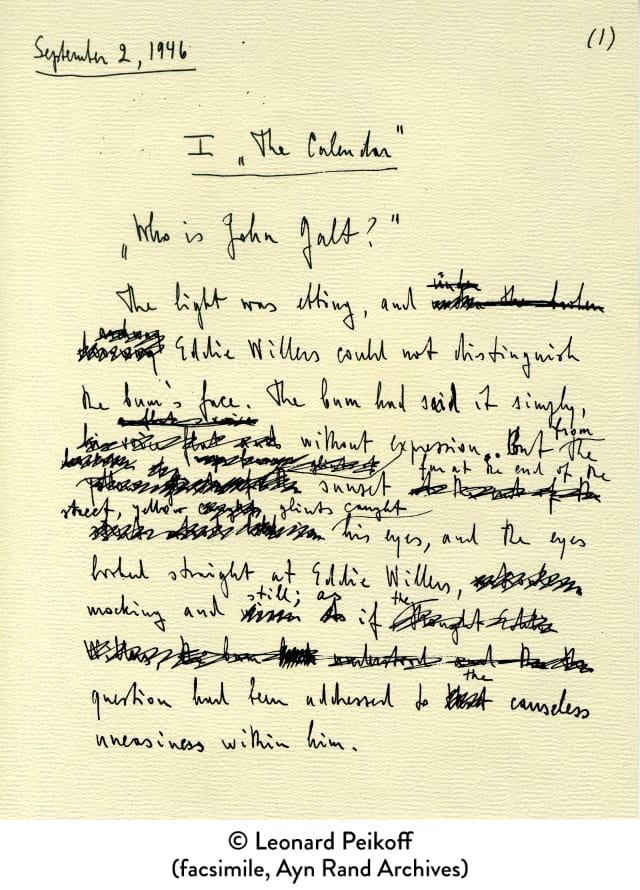

When an acquaintance told Rand she had a duty to write a nonfiction work about her philosophy, Rand formed the idea for what would become her major work: Atlas Shrugged. What if I went on strike against such a duty, she thought. What if all the creative minds went on strike? As she started the novel, she realized that issues more fundamental than ethics were involved. This led her to the identification of a range of philosophic ideas that would make her story and heroic characters possible. It took her thirteen years to complete a novel that dramatized “the role of the mind in man’s existence.”

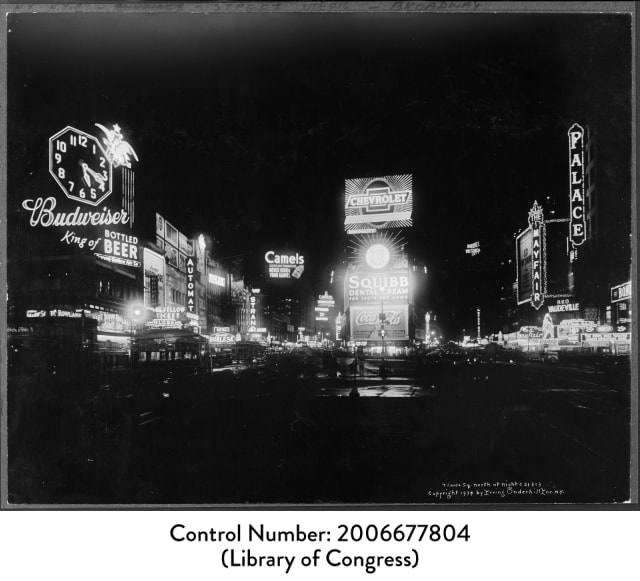

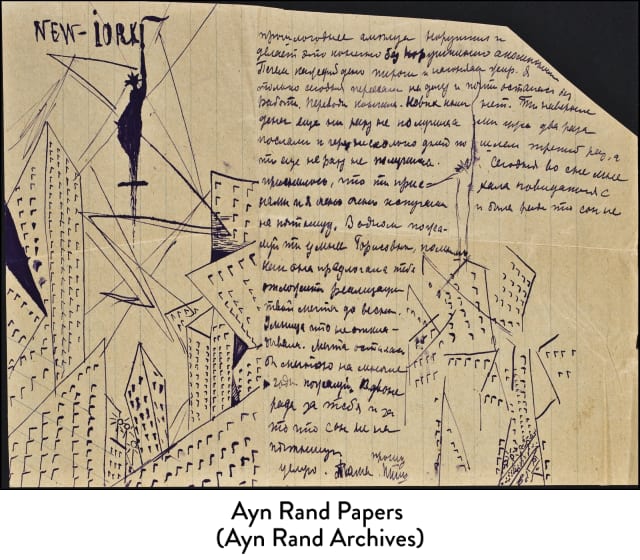

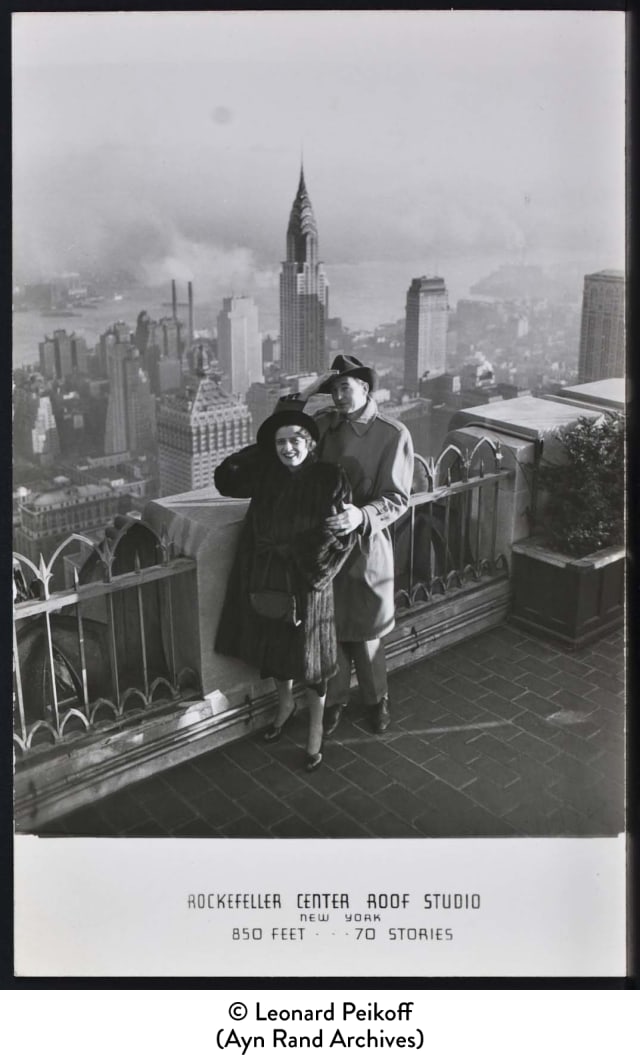

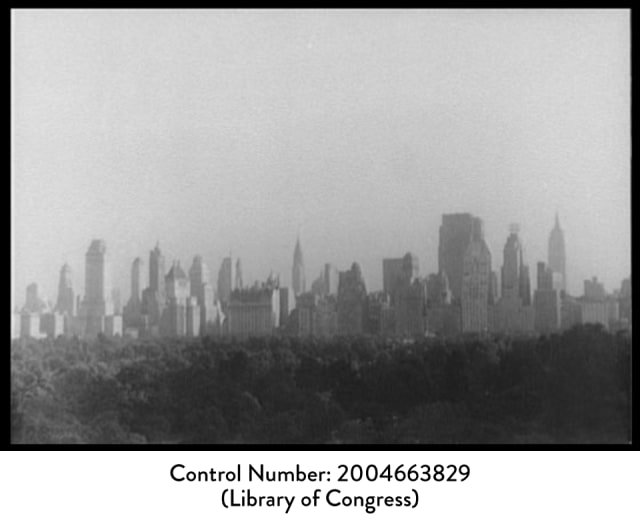

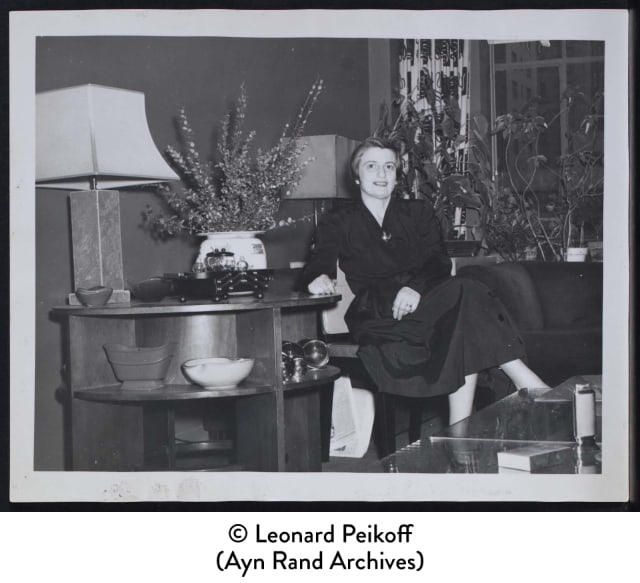

In 1943 Rand wrote in a letter from California: “I’m in love with New York, and I don’t mean I love it, but I mean I’m in love with it. Frank says that what I love is not the real city, but the New York I built myself. That’s true.” Nearly eight years later, in the fall of 1951, she and Frank finally drove back to Manhattan, where she lived the rest of her life. While in Russia, she had sat through multiple screenings of American silent films just to get a glimpse of Manhattan. With its high energy, productivity and skyscrapers, New York meant America to her.

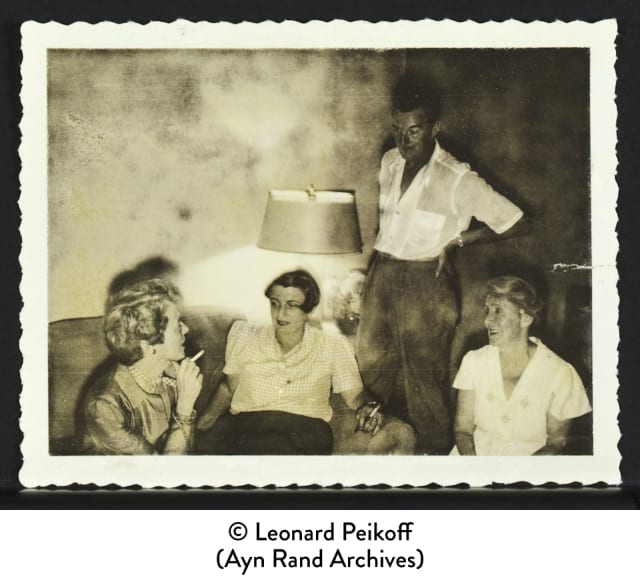

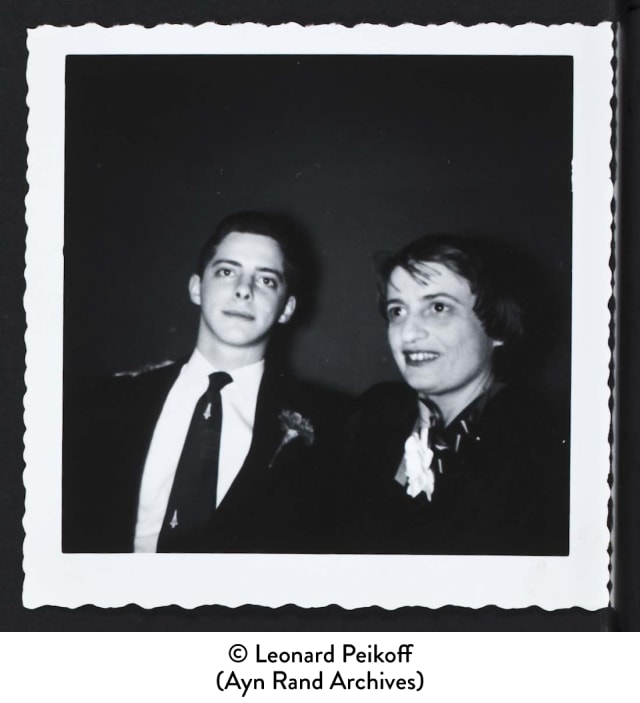

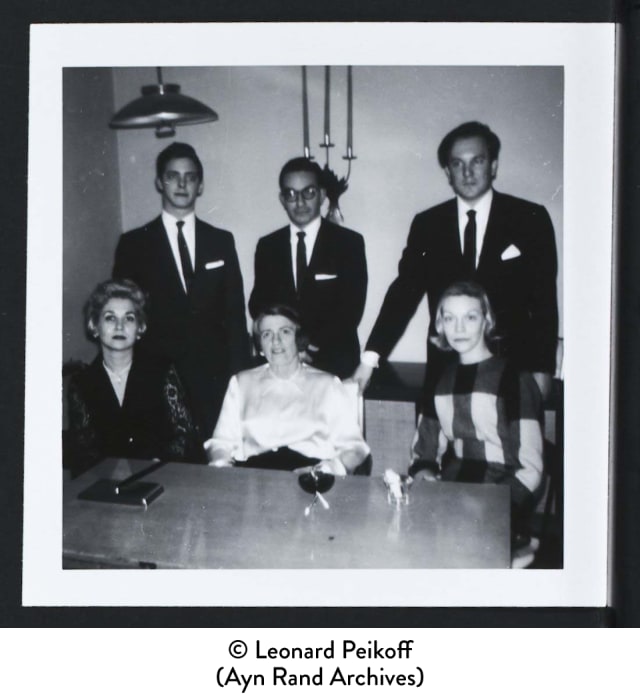

Beginning in the early 1950s, Rand’s friends were mainly a group that she jokingly called “The Collective.” They met informally to socialize, discuss ideas and even read the manuscript of Atlas Shrugged. This group was also instrumental in starting the Nathaniel Branden Institute, formed in 1962 to promote Rand’s philosophy. NBI presented both live lectures and taped courses, which were distributed throughout the world. It also maintained a book service and occasionally sponsored social events. NBI continued until 1968, when Rand broke with Branden over personal and professional issues.

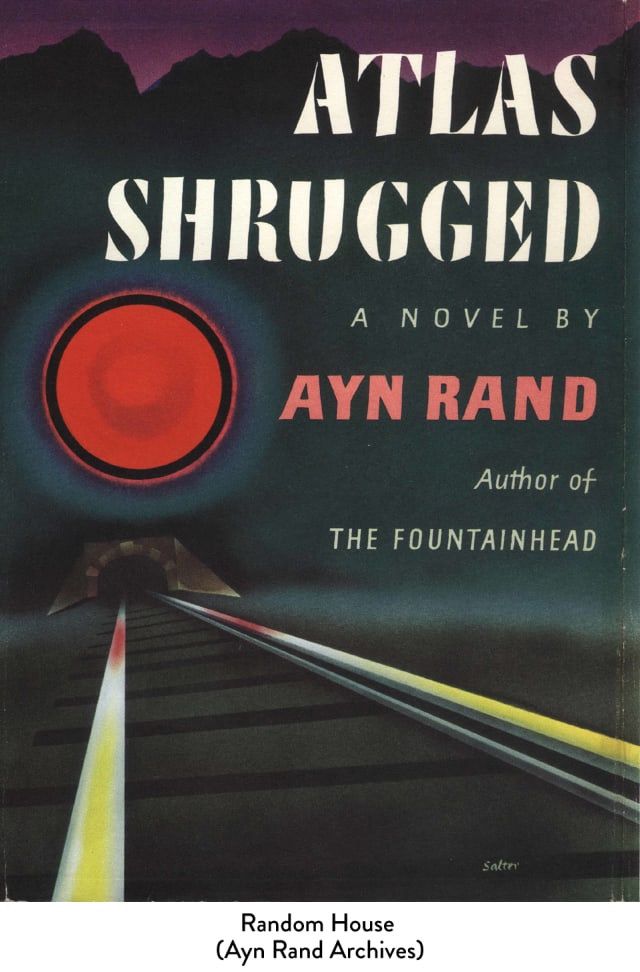

With the publication of Atlas Shrugged in 1957, Rand’s world changed. If The Fountainhead had made her famous, Atlas Shrugged made her a controversial figure for the rest of her life. There was now no doubt where she stood philosophically: she was the foremost philosophic defender of capitalism, egoism and reason, and an opponent of collectivism, altruism and religion. In contrast to the polite and often positive reaction to her other novels, the response to Atlas Shrugged was principally negative and often vicious. A best seller for nearly five months, it has sold more than eight million copies.

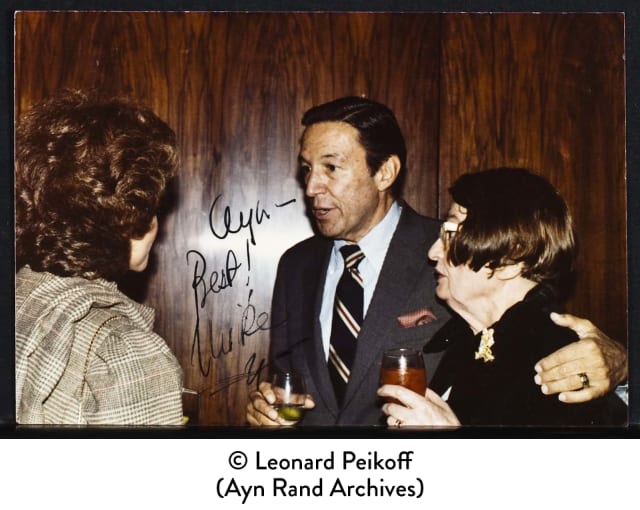

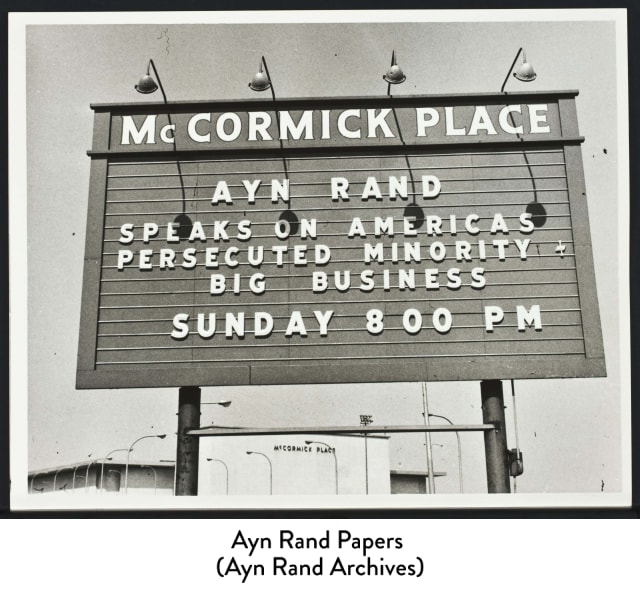

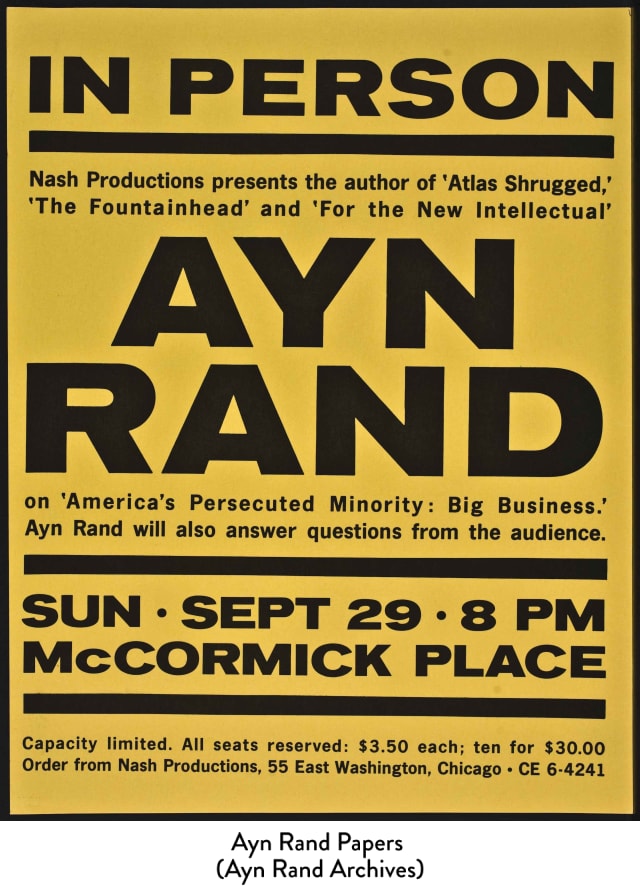

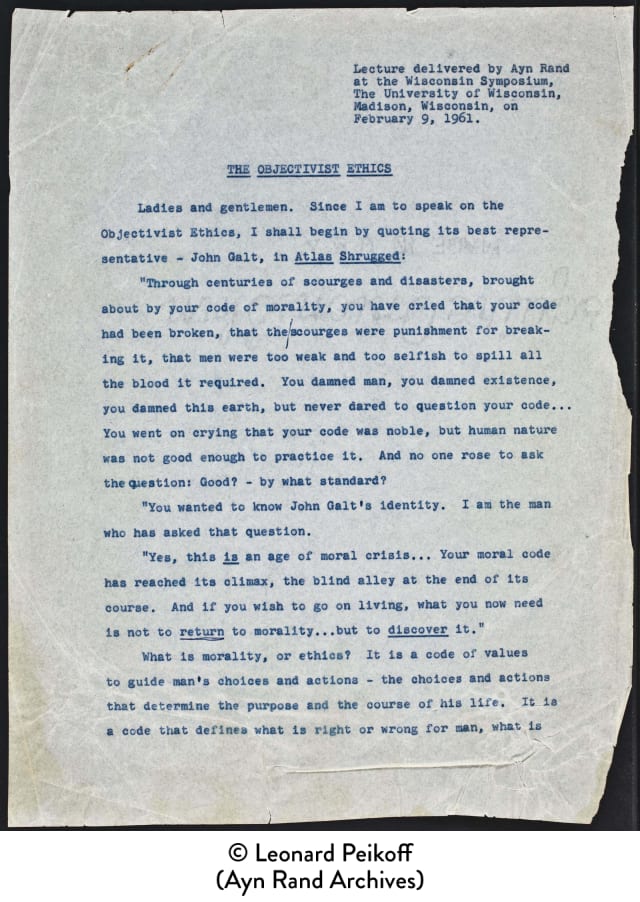

Not willing to stand by while Atlas Shrugged was misrepresented and almost universally attacked by the critics, Rand undertook the task of explaining her philosophy. “I began to see that what I took as almost self-evident, was not self-evident at all.” Carrying her message to students and the public, she gave talks on her philosophy (which she named “Objectivism”) at university campuses from Wisconsin to Yale, had her own radio programs on two FM stations in New York, and made dozens of radio and television appearances on shows hosted by Mike Wallace, Johnny Carson, Phil Donahue and others.

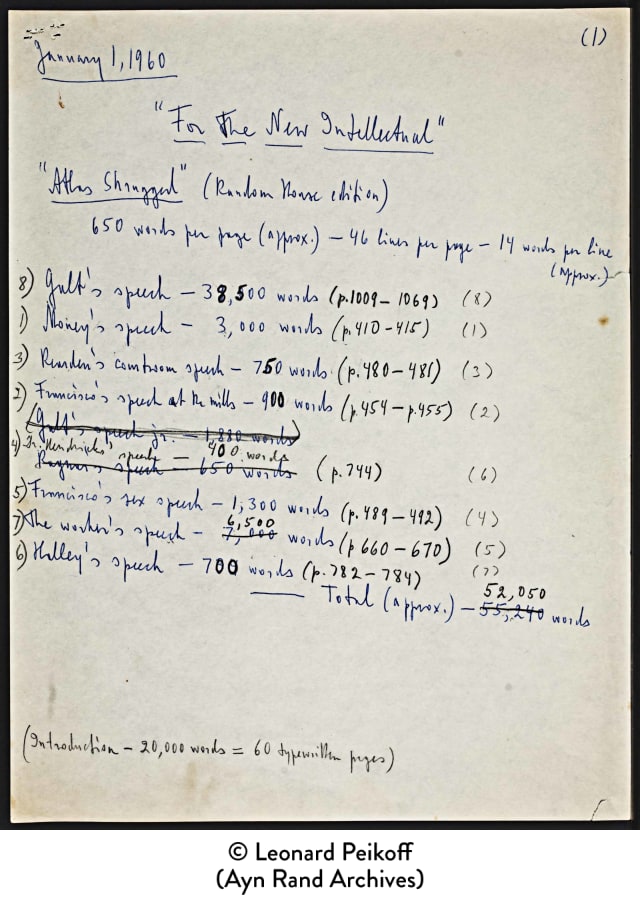

Rand’s first nonfiction book, For the New Intellectual, was published in 1961. It contains the main philosophic passages from her novels, but it was the title essay that brought her to the attention of the academic community. In that essay she explains that Western civilization is a clash between man the thinker and producer and his enemies, the men of faith and the men of force. If civilization is to survive, she argues, it must reject mysticism and the morality to which it leads (altruism), and replace these with a new philosophy of reason and rational self-interest.

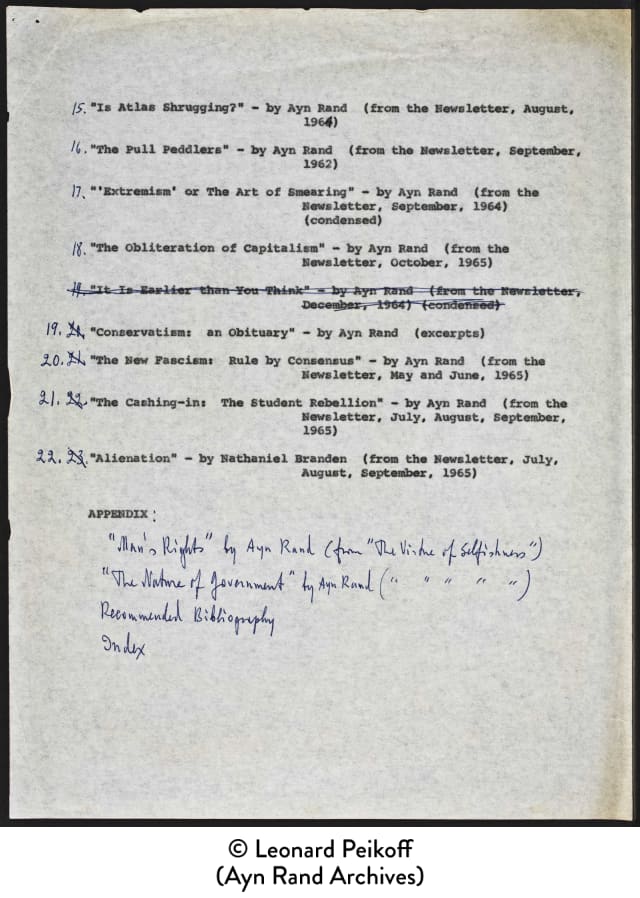

In January 1962 Rand launched the first of several periodicals, the monthly Objectivist Newsletter. It was replaced four years later by The Objectivist and then in 1971 by the bi-weekly Ayn Rand Letter, which ceased publication in early 1976. These periodicals contain articles on philosophy and its application to a wide variety of topics (from art to politics to current events), as well as book reviews and events of interest to her subscribers.

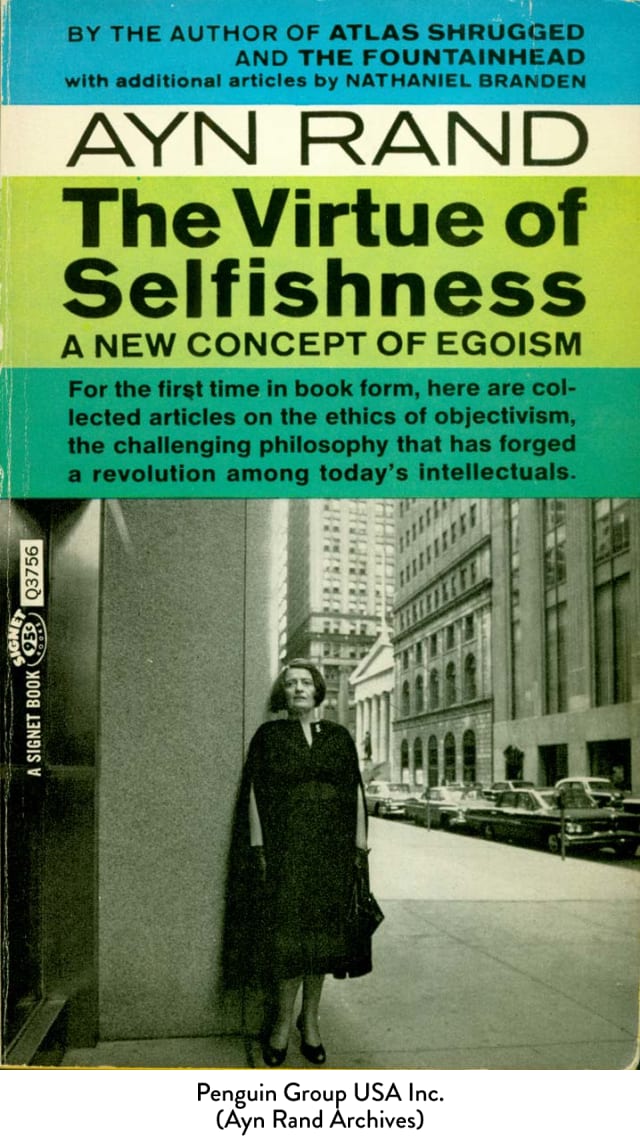

The Virtue of Selfishness (1964) is a compilation of articles on ethics, largely from her newsletter, and presents the essentials of Rand’s “new concept of egoism.” The Objectivist morality, she explains, is based not on religious faith or on majority opinion, but on the factual requirements of human survival. According to her new theory, each individual should live for his own happiness, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself. The book contains important applications of her morality to such topics as man’s rights and the evil of racism.

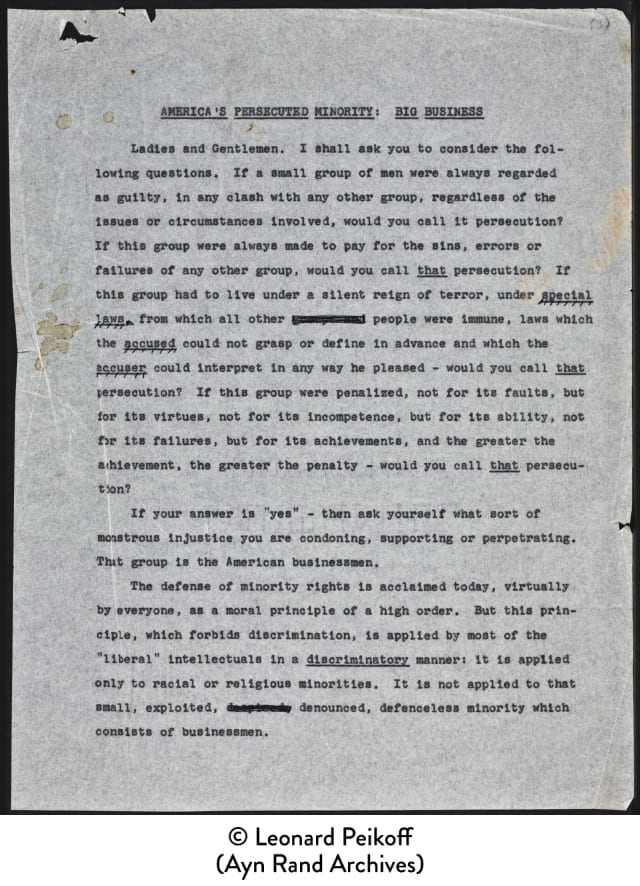

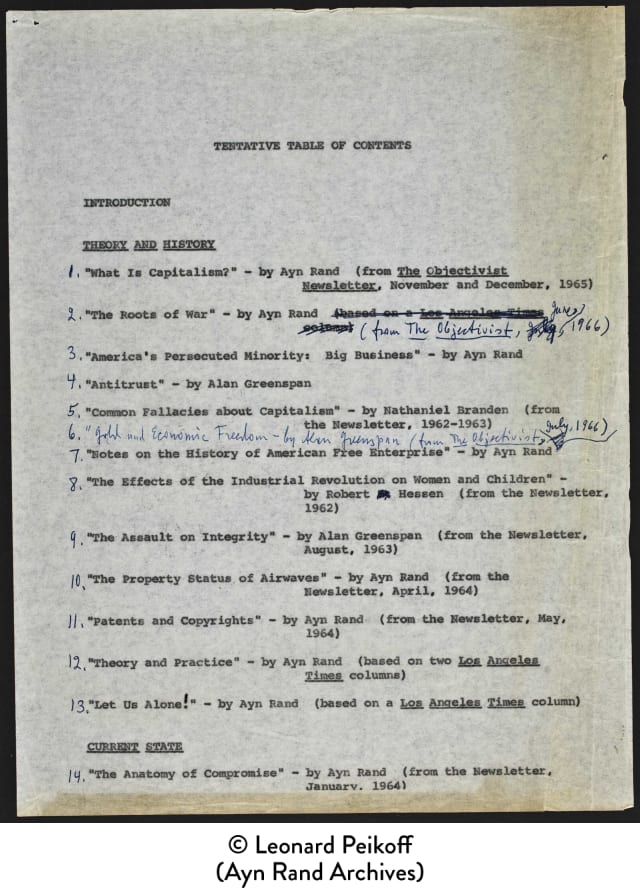

Capitalism, in Rand’s view, has long been attacked as immoral, and its true history has been subject to widespread distortion. This 1966 collection of essays seeks to correct some of these historical and economic myths, while offering a moral defense of capitalism as “the only system geared to the life of a rational being.” The book is not a treatise on economics, but a collection of essays on the philosophy of capitalism: the basic truths and principles that make capitalism the only moral and practical social system.

This is Ayn Rand’s call to American youth to reject the destructive ideas of the New Left in favor of “a philosophic revolution founded on the supremacy of reason.” It includes a tribute to space exploration, analyses of the deplorable state of education, and a critique of environmentalism (which she labeled “the anti-industrial revolution”). An edition (Return of the Primitive: The Anti-Industrial Revolution) revised after her death includes essays by Rand on racism and tribal collectivism, along with critiques of environmentalism, feminism and multiculturalism by editor Peter Schwartz.

In this 1975 collection of essays called The Romantic Manifesto, Rand presents her original theory of art. She explains the philosophic “nature of art and its importance in human life,” emphasizing the differences between Romantic literature (which presents man as volitional and heroic) and Naturalistic literature (which presents man as a helpless victim). She also discusses why art has such a profound and personal impact on the viewer, analyzes the basic principles of literature, describes the goal of her writing, and explains her view of what is and what is not art.

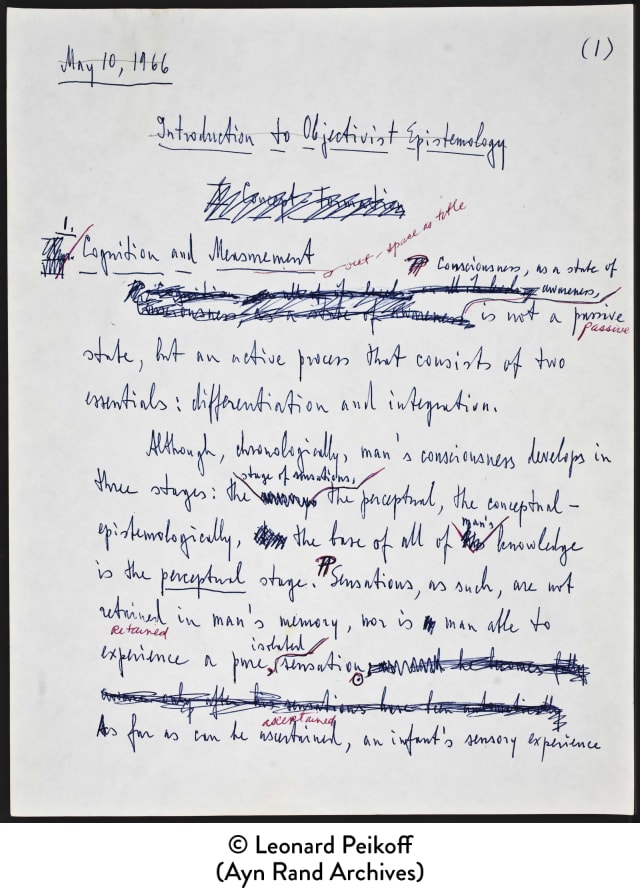

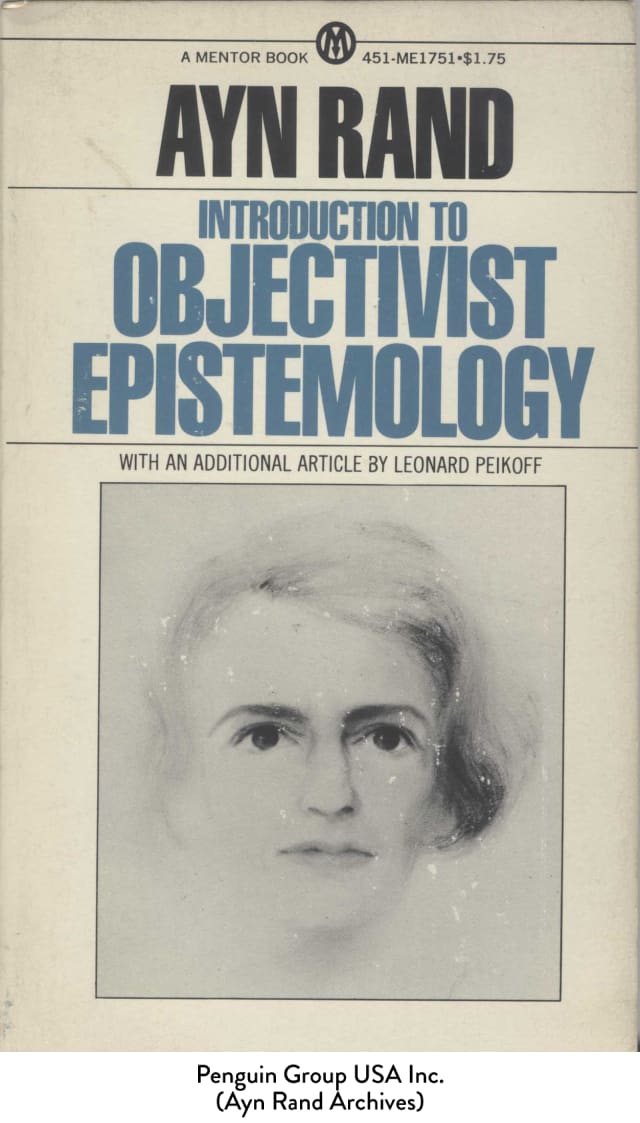

For Rand, philosophy is the power that determines the life of an individual and a culture. And the most important branch of philosophy, she held, is epistemology, the study of knowledge. Human knowledge is held in the form of concepts; if our concepts refer to nothing in reality, then reason is worthless. Establishing the validity of concepts has been a philosophic problem since ancient Greece. Rand took on this problem and presented her solution in her most technical work, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology. With it, she aimed to vindicate man’s mind and show its efficacy and power.

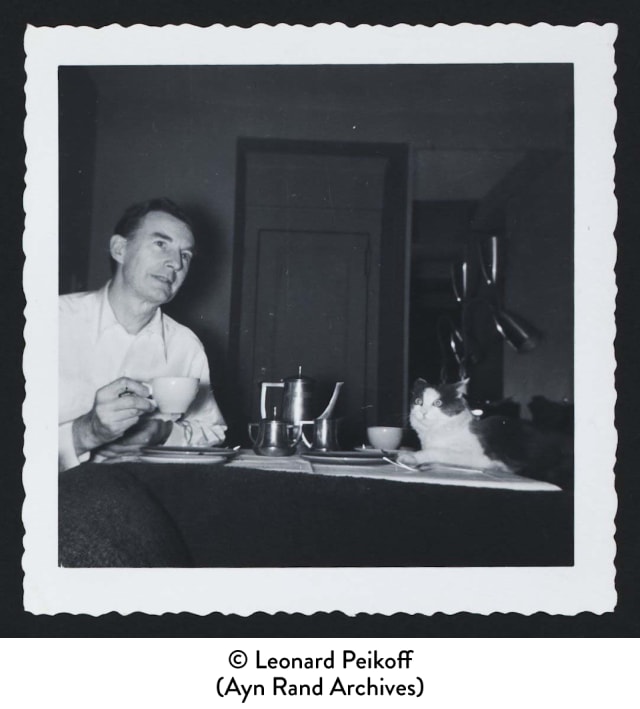

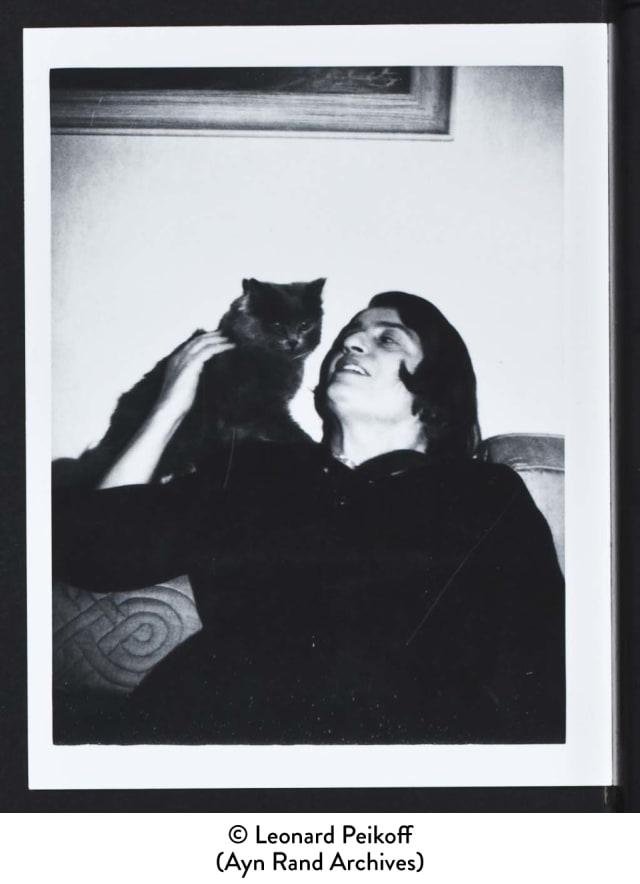

Rand’s top values were her career and Frank O’Connor. But she had many concrete values that exemplified her view that the purpose of morality is to enjoy one’s own life on earth. She loved her cats (whose names included “Los Angeles,” “Frisco” and “Tommy” for Thomas Aquinas), and she greatly enjoyed music (she left a large record collection), stamp collecting (she wrote an article titled “Why I Like Stamp Collecting”), and a group of friends with whom she engaged in marathon philosophic discussions. She lost her top value when Frank died on November 9, 1979.

Rand held that each one of us is guided by philosophic ideas, whether we know this or not and whether we choose to think about ideas or not. And these ideas have real consequences in our lives for better or worse, depending on whether they are rational or irrational, true or false. This essay collection, the last work planned by Rand before her death in 1982, brings together pieces of hers that touch on the theme of philosophy’s indispensable role in human life. The title essay is a talk that Rand gave on this subject to the 1974 graduating class at West Point.

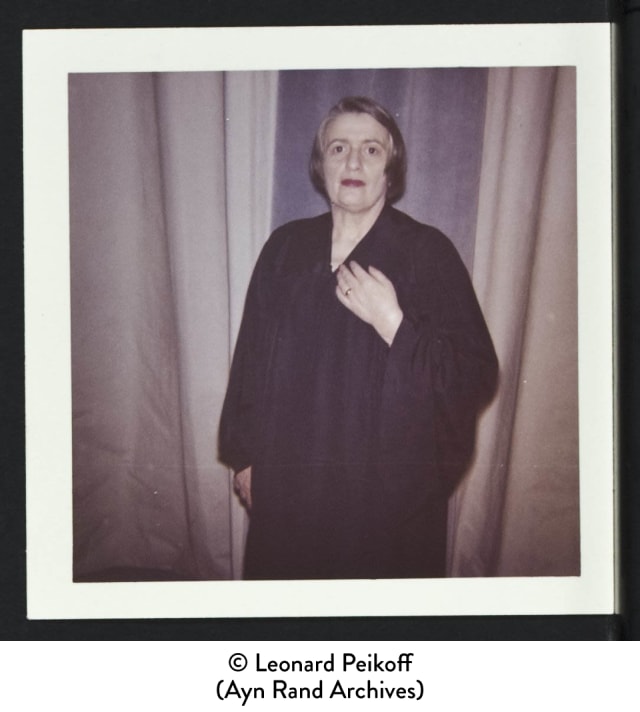

When Ayn Rand’s life came to an end on March 6, 1982, she had more than fulfilled her father’s prediction that she would leave a large mark and become world famous. After escaping the poverty and tyranny of Soviet Russia, she had become a successful screenwriter and playwright, a best-selling writer of novels that change people’s lives, and the originator of a new philosophy that is now studied in university classrooms. Her last line from a series of biographical interviews recorded in 1960–61 could sum up her view of life: “It’s a benevolent universe.”